The Brookline Bird Club: 1913-1945

On June 18, 1913, thirty birders gathered at the Brookline Public Library to found the Brookline Bird Club. Their object was “to study, observe, and protect native song birds and to encourage their propagation.” Inspired by a lecture by Ernest Baynes of the Meridan Bird Club in New Hampshire, Mary Moore Kaan had organized the meeting and posted notices in The Brookline Chronicle and The Boston Transcript. A front-page Chronicle article, “BBC Organizes to Protect Native Singers and Wild Species,” reported that the club was formed “to study ‘the little brothers of the air,’ arouse a sentiment for their preservation, arrange free lectures for the people, and plan other ways of education in bird life.” The BBC established a constitution and set dues at 50 cents, 25 cents for “juniors”-boys and girls under 14 but “old enough to go alone on street cars.” The first officers were Edward M. Baker, president; Charles Floyd, vice-president; Ada Chavelier, secretary; and George Kaan, treasurer. Eight women and three men served as the first directors.

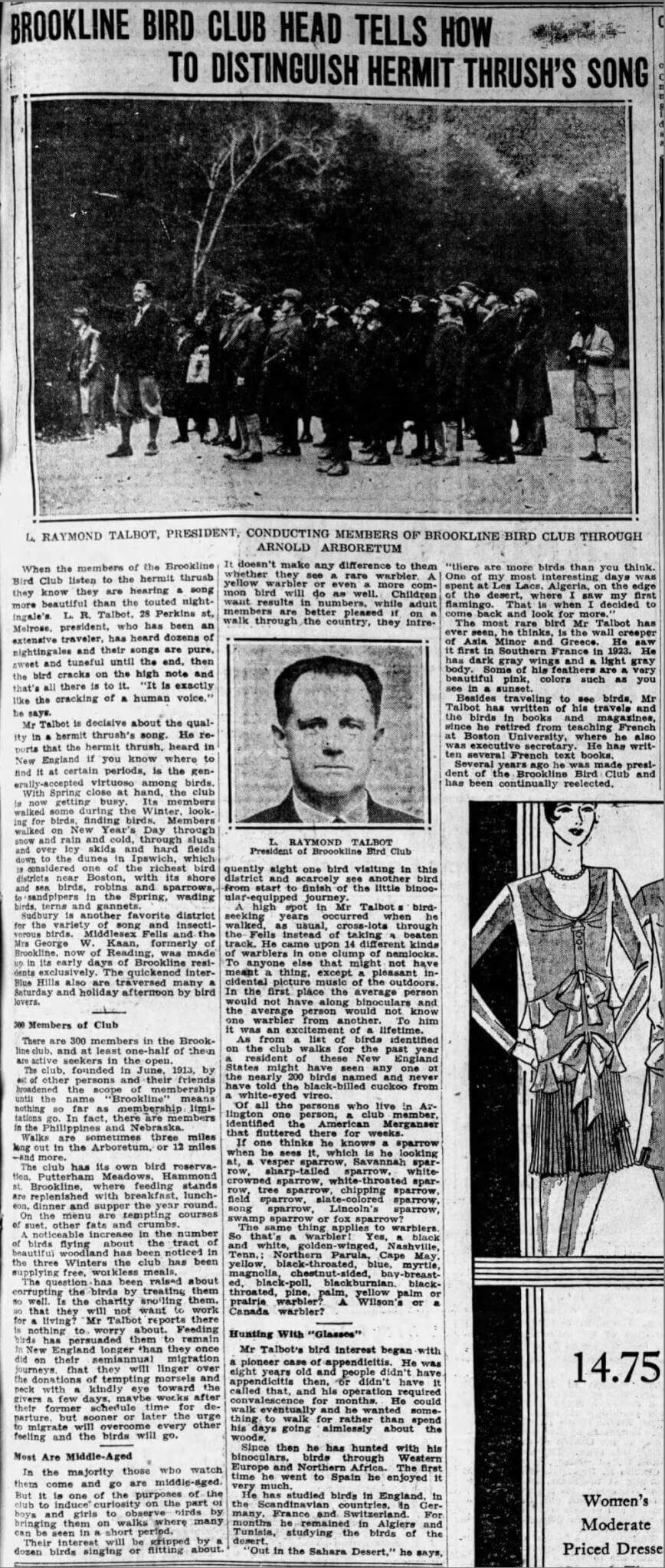

The first club bulletin announced five walks in fall 1913, all in or near Brookline. On the first walk, led by Edith Hale, 24 members found 14 Bobolinks and two pairs of Ring-necked Pheasants at the Cambridge marshes on September 27. Other trips that fall headed to Jamaica Pond, Franklin Park, the Chestnut Hill woodlands, and the Boston Public Garden, where the group was gratified by a Hooded Warbler in breeding plumage, described in fine detail in the Chronicle. For decades, trip leaders wrote reports of “club rambles” for the Chronicle, with complete lists of species seen-Evening Grosbeak in West Roxbury in 1914; Common Redpolls, Pine Grosbeak and Acadian (Boreal) Chickadee at Jamaica Pond in 1916; an albino crow in that fairly echo in the spring.” A Boston Globe photo in November 1913 captured the BBC group, led by Charles Floyd, at Chestnut Hill: men in suits and ties, women in bulky ankle-length dresses, all wearing (unplumed) hats, and one junior in the front row.

200 people attended the first annual meeting in February 1914, with a lecture by state ornithologist Edward Howe Forbush on “Useful Birds and Their Protection.” Across the country, countless birds were still being shot, for food or “sport” or as alleged pests, and Forbush, like Alexander Wilson a century earlier, felt compelled to justify their preservation on grounds of utility as well as their beauty and fascinating behavior.

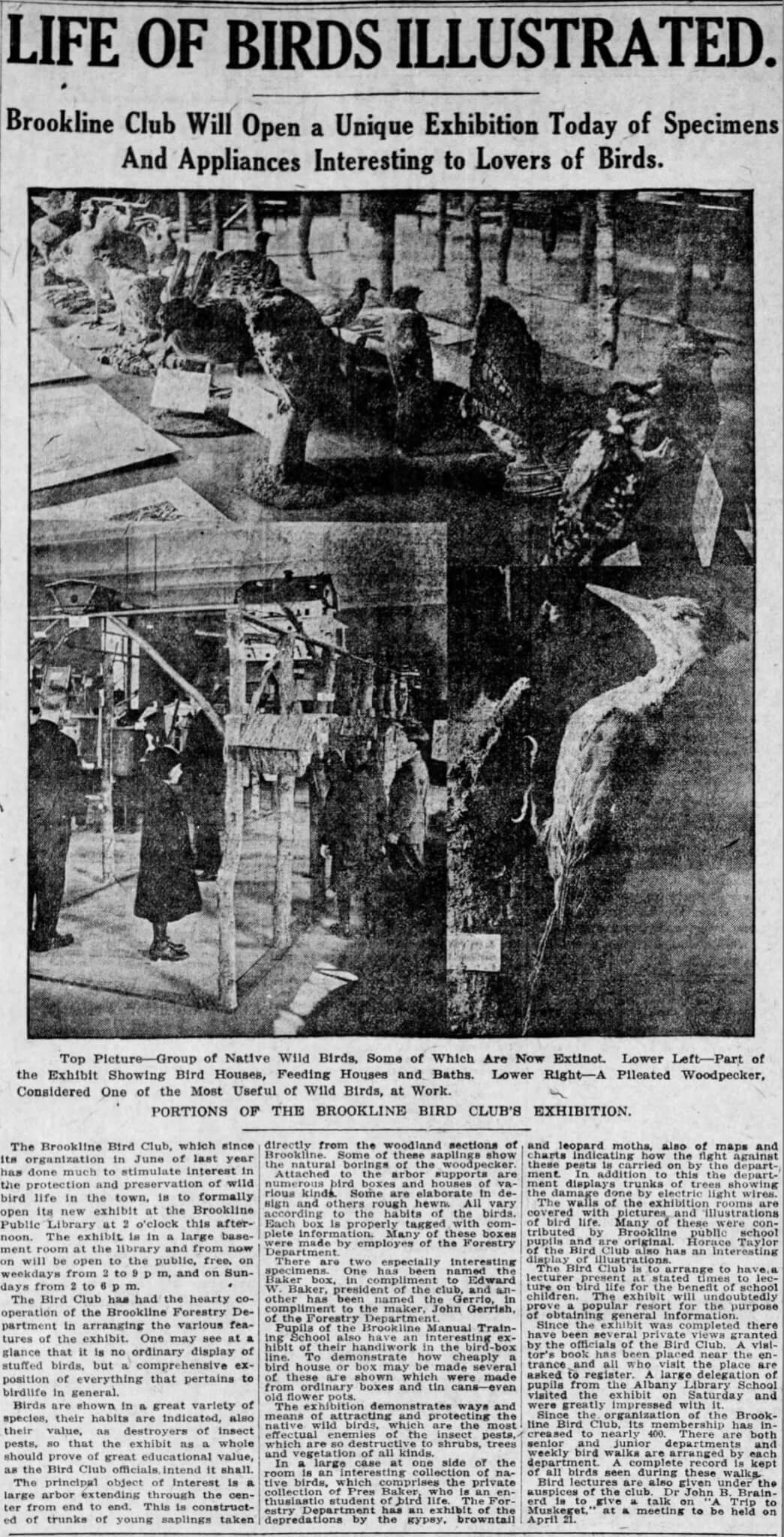

Life of Birds Illustrated

Boston Globe April 6, 1914

It’s no accident that one of the country’s oldest, largest, and most active bird clubs began in metropolitan Boston. Massachusetts, with its tradition of nature study, provided fertile habitat for a fledgling bird club. Birds graced the New England literary tradition, from Hawthorne’s hummingbirds, “like spiritual visitants,” to Melville’s “mysterious humming-bird of ocean” (a storm-petrel) to Emily Dickinson’s bird with “rapid eyes” like “frightened beads.” In 1818 the state had passed the nation’s first law protecting certain songbirds (or “non-game” birds) from shooting. In 1883 the Nuttall Ornithological Club, led by William Brewster, was founded in Cambridge. From Nuttall (still going strong) emerged the American Ornithologists’ Union, North America’s preeminent ornithological organization. The Massachusetts Audubon Society, founded in 1896, had led the fight against the plume trade. Towns like Cambridge and Concord had been regularly birded for decades, and the Chronicle, with perhaps a touch of hometown bias, boasted that Brookline was “probably the center of bird interest in the United States.” The town had its own bird warden, forbade the use of firearms or traps for birds, and by 1915 was distributing sleigh from stop to stop.

The BBC did not aim to be a society of birding authorities but rather an egalitarian group welcoming all comers, rookies and veterans, men and women, young and old, to “know birds and enjoy them” and gain “a fuller appreciation of nature.” It was not a social organization but offered the camaraderie of watching and learning about birds in good company. At a time when professional ornithology was an exclusively male domain, the full involvement and leadership of women, including the prime mover and the first trip leader, distinguished the club. Decades before they gained the right to vote, women had led the Audubon campaign against the plume trade-what Chris Leahy has called “the first successful wildlife protection movement.” Poet Celia Thaxter had chastised any woman who would wear “a charnel house of beaks and claws and bones upon her fatuous head.” By 1900,”bird rambles” had become popular at Smith and other colleges, and women were publishing books like Florence Merriam Bailey’s Birds through an Opera Glass and Neltje Blanchan’s Bird Neighbors (150,000 copies sold).

Women also worked to setup Junior Audubon clubs and were especially determined to convert children to the pleasures of birding. This determination was shared by the BBC founders, who made “special reference to the status of children in the club” and believed that even boys who shoot or stone birds “can be made over into conservationists.” Bulletins urged members to bring juniors on walks. One bulletin insisted that the BBC had a “sacred obligation” to cultivate young birders. By 1915 the club had over 100 junior members. In 1920 juniors represented almost 30% of club membership.

The Junior Department, which had its own bulletin, was led by Horace Taylor, who, the Chronicle noted, took “especial charge of these young people, leading them on instructive bird walks and continually counseling them in the best methods of bird study and bird protection.” Taylor’s tutelage encompassed birding-by-bicycle in Brookline and Cambridge, lessons in drawing birds and conducting a bird census, field contests in naming birds, and visits to the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology and the recently opened aviary at Franklin Park Zoo. He offered a series of illustrated lectures, “Our Bird-Life in the World,” to provide “fundamental facts of ornithology” without being “too scientific and technical for amateur or child.” A crowd of 277 attended one 1927 lecture. For years, the BBC sponsored a Brookline Bird Day at the Children’s Museum. BBC leaders observed that “some of the most useful members came into the club as children.” One example was Richard Pough, who went on to lead club trips while a biology student at M.I.T and ultimately became a founder of the Nature Conservancy. Maurice Broun (curator of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary) and Roger Tory Peterson were both active in the club as young men.

In May 1915 the BBC helped organize a State Bird Day at Franklin Park, with a welcome address by Boston mayor James M. Curley. The club led walks and set up a “bird protection” exhibit in the Brookline library that drew visitors from as far off as Texas and featured bird houses, a lecture on bird symbolism in art and literature, a Brookline migration chart, a display on “bird enemies” (snakes, squirrels, owls, shotguns), and work by junior “essayists and artists.” Winston Packard’s Chronicle article, “Brookline Wants Woodpeckers,” reported that President Baker shared his “splendid collection of mounted native birds taken by him within the limits of what is now Brookline,” and praised Baker as a “man who long ago learned that it is better to hunt birds with opera glass and the camera and who consistently devotes his energies to the spreading of that gospel.” The article lauded the BBC nest box program for bringing “great economic as well as aesthetic value” to the community. A Boston Evening Transcript article on the exhibit, by Packard and Ernest Baynes, countered this emphasis on economics: “All but particularly stupid or particularly thoughtless people must be interested in birds entirely apart from their economic value, and to many they are the source of the greatest joy.”

Bird walks have always been the club’s main activity, but from the start, many club leaders viewed these walks as a means toward conservation, not the club’s purpose. In his open invitation to join the BBC, President Baker spelled out the club’s goals: “stimulation of interest in bird life” but also “protection of our local wild birds,” “gradual establishment of a bird sanctuary,” and “protection against the insect pests.” In 1913 The Christian Science Monitor reported that the BBC followed “all legislation that would affect the welfare and culture of birds” and was lobbying to forbid the importation of feathers-a proposition that would pit “friends of birds” against the French Syndicate of Feather Workers. A 1929 bulletin flatly proclaimed: “The primary purpose of our Club is to protect birds.”

Locally, the club recruited residents to set up winter feeding stations-“please feed the birds”–contributed to the Arnold Arboretum Endowment, lobbied successfully for a law to stop the shooting of Bobolinks, encouraged members to share “old bird glasses” with novices, and, in cooperation with the Brookline Park Commission, established the Putterham Meadow Sanctuary in 1926. In 1919 the BBC allied with Mass Audubon, with which it maintained “pleasant and mutually helpful relations,” to stop development on Plum Island and preserve the land as a state bird reservation. Nationally, the BBC worked to pass the Migratory Bird Treaty in 1918 and in 1922 endorsed the Bird Banding Association. BBC officer Charles Floyd served as a councilor for the Federation of the Bird Clubs of New England, which maintained that clubs “have a real duty to perform in assisting in the work of bird conservation.” The Federation helped to establish sanctuaries on islands off Chatham, Lynn, and Rockport; protected coastal tern colonies; made “a final attempt to save the Heath Hen from extinction;” and campaigned “to stop the iniquitous practice of abandoning housecats, THE GREATEST ENEMY OF THE BIRDS.”

Another conservation battle was the fight against the English sparrow-a continuation of the 19th century Great Sparrow War, when defenders and attackers of House Sparrows had vilified one another, and the birds themselves, as liars, traitors, and murderers. At an early club meeting Horace Taylor reminded members of “the imperative need of getting rid of the dirty, noisy English sparrows who,” according to the slightly stunned Chronicle reporter, “had not a friend in the company to stand up for them.”

The BBC’s early years also reflected a nation in wartime. In 1917 the club called for a boycott of “war wings,” feathers sold to women by the Naval Reserve in the name of “national service.” The next year, Army private E. Saxe, a club member, wrote a letter from France thanking the BBC for its trip reports in the Chronicle and asking for ID help with a “warbler type” bird singing joyfully at dawn just after his company was gassed in trenches by the Germans. In 1919 Barron Brainerd, a birding prodigy, club director and Nuttall member just back from the war, died at age 26. His grieving father, BBC president John Brainerd, led a trip to Point of Pines in Revere four months later.

Club membership quickly grew and spread beyond Brookline, as did trip destinations. Membership hit 200 in 1914–when a life membership was established and the BBC joined Mass Audubon–passed500 by 1920, and reached 558 in 1928. In December 1913 the BBC offered its first trip, by boat from Rowe’s Wharf in Boston and then by narrow gauge railroad, to the Lynn and Nahant beaches. A year later, 39 members went to Marblehead Neck. The first trip to Cape Ann, via the Boston-Gloucester freight boat, was in early 1916; the first to Duxbury, June 1916; the first to Moose Hill Sanctuary in Sharon, May 1921. Some trips involved long, demanding hikes, from Greenbush to North Scituate (sometimes by snowshoe) or from the Ipswich railroad station along the dunes of Crane Beach to the Essex River mouth. Members were warned to dress warmly in such frigid, remote territories as Nahant. “Bird Club Members Brave Cold, Wind and Snow” and “Five Brave Blizzard to Visit Marblehead” read the headlines of stories about trips in 1916 and 1919. A report on a March 1916 Brookline trip provided more proof of birders’ heartiness: “We tramped through the fields of snow, over the hills and around the swamps, with the wind blowing the snow in our faces . . . most enjoyable.” Undaunted, club members went out the next day and found a Northern Shrike eating an English Sparrow.

Sometimes the challenges were human. Trips to Jamaica Pond had to contend with children frolicking in the parkway as well as “barking dogs, nursegirls pushing squeaking baby carriages, equestrians, pedestrians, motorists, ball-players, picnickers, and what not.” In 1919, an author named Nuthatch wrote a satirical trip report about a group of hunters, the Jungle Klub, riding borrowed circus pachyderms, that headed to the Lynn marshes to shoot Jungle Kreatures but were frightened off by weird, opera-glass-wearing bipeds who muttered incomprehensible things like “whatawonderfuljunco.”

For years, club bulletins provided instructions for train and boat connections, as well as costs. Leaders were expected to be well-versed in train logistics and to “tactfully” solicit new members. Horace Taylor implored all members to keep careful bird lists as a storehouse of valuable scientific data. Leaders were never expected to be authorities, but in a period of intense controversy over the reliability of sight records, they were encouraged to be scrupulous in identification and maintain exact counts of species seen, even English Sparrows. Women and men shared club leadership; of the 42 walks in spring 1922, women led 26. In 1923 the BBC doubled its dues to $1-still the cost of dues a half century later. Juniors were now charged 50 cents. A life membership went for $10.

Early lectures included bird mimicry performances by the noted “whistler” Arthur Wilson and by Charles Gorst, who whistled “operatic airs with Victrola accompaniment;” a round table discussion of finches; a recital of “Songs about Birds” by club director and “dramatic soprano” Edith Torrey (singing Shakespeare’s “Where the Bee Sucks” and “Hark! Hark! the Lark”); and topics ranging from the focused “Hunting without a Gun” to the not-so-focused “Random Observations on Birds.” Later lectures reflected both a growing interest in birding beyond Massachusetts and changing technology. In 1914 Forbush used a “stereopticon” for illustration (it malfunctioned); in 1918,” lantern slides.” By the late 1930s “Kodachrome pictures” provided the graphics. In the mid 1920s the BBC, as part of the Federation of the Bird Clubs of New England, helped to get state funding for Forbush’s comprehensive and engrossing Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States, which became a standard guide, though, in three volumes, it was expensive and too heavy and cumbersome for easy field use.

A 1925 bulletin bemoaned disappointing attendance at meetings but stressed that the club was “flourishing,” with large attendance on walks. That year the BBC sponsored a Memorial Day trip to Plum Island and three-day excursions to Cape Ann and to New Salem in central Massachusetts, where the group found nesting Olive-sided Flycatchers. As early as 1918, some members had driven to an outing in the “quaint city” of Ipswich, but the first all-automobile trip, to Artichoke Reservoir in West Newbury, didn’t occur until 1930. The BBC also worked in tandem with Mass Audubon to run a bird-study camp at Echo Lake on Mt. Desert Island in Maine. Some members began birding internationally. In the 1920s club president Raymond Talbot led several versions of his “Nature Study Tour of Europe,” a mix of birding, nature hikes, and cultural sightseeing. The 70-day 1926 tour steamed out of Montreal on the Cunard line’s S.S. Ascania and crisscrossed northern Europe by rail and motorcar, at a cost of $980 per person. Of the 137 species seen, a “rare” Merlin in Grasmere, England was a life bird for the leader.

Of course, local birders didn’t have to go to the Lake District to find birds. With a little imagination we can share the excitement of BBC members in 1926 as they watched an Arctic 3-Toed Woodpecker in Wellesley; a Rose-breasted Grosbeak and Scarlet Tanager “singing lustily” side-by-side in Framingham; Red-headed Woodpeckers near the Brookline library; a White-winged Crossbill at Putterham Meadows; a Pine Grosbeak in Winchester; a Northern Shrike catching a mouse in Belmont; a Northern Goshawk biting off a rooster’s head at a Wellesley farmyard (not witnessed on a club trip, but reported); a Pacific Loon and three “booming” Heath Hens on the club’s first trip to Martha’s Vineyard; or a few of the nine Snowy Owls seen one November day in Ipswich, Cape Ann and Marblehead. 1927 brought more good birds:7 Puffins and 4 Dovekies on a stormy January day in Nahant, a Brunnich’s (Thick-billed) Murre off Marblehead Neck, and, at year’s end, wintering Evening Grosbeaks in Norwood.

A 1928 Christian Leader article, “An All Day Trip in Agawam,” gives us a feel for a typical BBC outing of the period, a May day trip to Ipswich (originally named Agawam). To join the walk, the author, Johannes (no last name given) from Brookline, had to overcome “trip resistance”-the “natural human dislike of spending a few hours on company tension with strangers.” This tension was eased by the friendly leader, an unnamed Waltham librarian, who “put himself out” to get beginners on birds. Johannes, sociologically inclined, divides his fellow participants into birding types: the chatty, sociable ones; the skeptics, who require rigorous proof for each identification; the go-alongs, with “the will to believe,” ready to take the leader’s word for any sighting; and the diehards, plunging headlong into thickets. Johannes also notes the group’s “traditional New England reserve,” a reserve instantly dropped when they came upon a Yellow-breasted Chat. Some participants stopped to play with children or dogs. Others, presumably not the diehards, strayed off in search of ice cream. At day’s end, while waiting for a boat on Plum Island, they all got a close look at a Piping Plover. Johannes ends his article with the hope that sportsmen and naturalists will join hands to save this struggling species.

Judge Larry Jodrey, in his 50th anniversary address to the club in 1963, also conjured up visions of BBC trips long before his own days as a birder. Before automobiles became common on trips, members would travel by train to far-flung locations like Newburyport. After long days in the field, they’d eat New England clam chowder and warm themselves around fireplaces in boarding houses or small hotels. Birding was more challenging, with inferior optics and reference books. Casual clothing of any kind was hard to come by, much less designed-for-birders outfits with big pockets and detachable leggings. Members often wore old business clothes, the “ladies crowned by hats not always currently in style” but without ear-rings, ornaments considered in poor taste on birding walks. “Jewelry and finery,” Jodrey observed, “were reserved for the indoor meetings to which the members customarily wore their dressiest outfits, rendering themselves sometimes unrecognizable to friends who were accustomed to seeing each other in birding garb.”

By 1930, BBC members also knew the bittersweetness Jodrey expressed-“a touch of sadness in recalling pleasant trips to many once delightful places which are now, on account of their development as residential and commercial areas, no longer birding territory.” On the club’s 15th anniversary in 1928, the Chronicle reported, “Unfortunately, the march of civilization has ruined many of the locations which were once favorite haunts of the birds.” In 1930, City Point in Boston-where a “rare” Hudsonian Godwit had been sighted two years earlier-was described as “again disappointing.” By 1931 Puttenham Meadows, once alive with birdsong, had become a “huge disappointment” and was eventually converted to a municipal golf course. A 1934 bulletin announced: “This may be the last club bulletin to list Belmont Hills among its trips.” The BBC was also losing some leaders to age and death. When she died in January 1931, Mary Moore Kaan was memorialized in a bulletin as a pioneer who had “instigated” the club “for the sake of the birds themselves” and “for the sake of the people.”

Despite these losses, the BBC carried on. The 1930 statistical report cited 476 members (including 49 life members, 4 honorary, and 26 junior); a high participant count of 34 in Nahant in February; a high species count of 84 in Ipswich on May 30; and a total count of 214 species on 133 walks. On an April 30 trip to Martha’s Vineyard, guided by Florence Little and longtime club ornithologist/statistician Grace Snow, members were among the very last people to see a Heath Hen. A census that year had found just one bird, which was allowed to live after some debate over whether it should be collected for science. It was the “last specimen of its kind,” Annie Stevens reminisced in a 1963 letter to club members, and a bird seen with “great satisfaction.” A Dovekie was found that same day. That October in Ipswich a Say’s Phoebe was seen but apparently not allowed to live, for it was “now in the Peabody Museum of Salem.” The statistical report concluded: “It pays to be a regular attendant on the walks.” A closing comment brought home the point: “We hope the reading of this list will make you envious” and “you will resolve to join our walks as often as possible.”

The 1930s stand out as a difficult but dynamic decade in BBC history. The main challenge was economic: the Depression. A few members dropped out; others requested more “ten-cent” walks to local spots that required no more than ten cents in carfare. Club leaders pointed out that many once “fine birdy places” had been ruined by development. 1934 was “the most difficult financial year in club history.” There were pleas to bring in new paying members, especially birders who might feel they’d “outgrown” the club. There was less money for bird protection. Yet the bulletin expanded beyond lists of trips and meetings to cover conservation issues in more depth and breadth, while including poetry from club members, like “Ipswich Dunes,” an “Italian sonnet” by Grace Haskell Story; whimsical pieces-how to prepare a “Christmas pudding” for chickadees; and wisdom from naturalists. One bulletin quoted Thoreau’s Notes on New England Birds: “I would rather never taste chicken meat nor hen’s eggs than never to see a hawk sailing through the upper air again.” Another quoted Donald Culross Peattie: “In Nature, nothing is insignificant, nothing is ignoble, nothing sinful, nothing repetitious. All the music is great music, all the lines have meaning.”

During the 1930s the BBC fought conservation battles on a wide variety of fronts. It argued for legal restrictions on billboards, opposed the practice of “duck-baiting,” proposed a tax on bird-killing housecats, and called attention to the damage done to shorebirds and seabirds by “waste pumped overboard from oil-burning vessels.” A 1930 bulletin listed by species the many oil-soaked dead birds found at Chatham Beach and Monomoy. Close to home, the club resisted a proposed highway with a toll bridge to connect Ipswich and Plum Island. Statewide and nationally, it embraced the campaign to stop the “wanton killing” of birds, especially birds of prey. In 1930, “standing four-square for the protection of birds of prey,” the club supported the federal Bald Eagle Protection bill, demanded enforcement of laws like the Migratory Bird Treaty, and resolved that “the names of all hawks and owls should be omitted from the list of birds not protected by law.” In 1934, while celebrating the foundation of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, the club criticized the spreading of “prejudice and false propaganda” about hawks and owls. President Talbot defended the “much maligned” American Crow, pointing out that many “innocent” birds were victimized by crow-shoots still common across the country. Bulletins acknowledged that members held conflicting views about hunting, but insisted that hunters should at least be able to “prove that you know the birds when you see them.” Some appeals ranged well beyond local birds-“Time for Action on the Tetons” and a reprinted plea to save the Australian Lyre-bird-or went beyond birds altogether, such as an attack on dog racing.

The BBC also renewed its efforts to nurture young birders. Leading the way was Talbot, who’d started birding at age eight during a long convalescence from appendicitis. In 1928, as educational field agent for Mass Audubon, he began writing Bird News for the School, distributed regularly to every high school and junior high throughout Massachusetts-free but with requests for contributions. In 1933 the BBC took over the publication, operating it at a loss, and sponsored prizes for the best student articles on bird-study or bird-protection. In Bird News Talbot demonstrated how to keep a nature diary and provided articles on topics like bird habits, seasonal variations, flycatching, the effect on birds of natural disasters, and reasons to go birding. “It’s always fair weather when bird-lovers get together,” he rhapsodized, even when the “mean, disagreeable” New England cold penetrates to the marrow. He fielded questions from readers: Do birds like to live in bird houses? Do they talk among themselves? How many birds does the average cat kill each year? Why do you like hawks so much? One student asked: “Is it possible to see an Ipswich Sparrow?” Talbot answered: “Possible, though not easy.” Another student wondered why a “stray Arkansas Kingbird” was still hanging around Cambridge in mid December. Talbot responded: some bird questions can’t be definitively answered.

Talbot also urged his readers to become bird protectionists. In a May 1934 piece on Martha’s Vineyard-a spot “almost sacred for bird-lovers”-he wrote, in bold: “America must learn, before it is too late, the lesson of the Heath Hen and of these other birds which Americans have destroyed. We must protect and save the birds we have left.” In a story about the “guardian of a large estate” who’d killed a Snowy Owl, he complained that the press too often treated such violators as heroes and singled out one paper as deserving “the severe condemnation of all right-thinking, law abiding people.” In one of his last pieces, about a birder with no interest in conservation, he concluded: “I have failed utterly if any large proportion of my readers really are convinced that conservation is of no concern to a bird club.” Talbot reached out to young birders with unflagging energy. For years, under his leadership, the club conducted dedicated bird walks for school, church, and scout groups. In 1940 alone, he gave 32 bird lectures at 21 summer camps.

Meanwhile, club trips ranged further afield and sometimes closer to home. The first BBC walk at Mt. Auburn was not until1934; the cemetery hadn’t been birded regularly until Ludlow Griscom and his followers began to go there in the 1920s. By the mid 1930s all-day auto trips had become regular. In 1936 the BBC conducted an “as the spirit moves us” auto excursion with no fixed itinerary. In May 1937 members traveled by car on the club’s first Big Day, with 107 species found, mainly in Ipswich and Newburyport. Bird highlights from the 1930s included a Carolina Wren in North Scituate in March 1931, an “unexpected” Holboell’s (Red-necked) Grebe on the 1937 Big Day, and on a November 1939 walk along the length of Plum Island, 2 Ipswich Sparrows, 2 Lapland Longspurs, an Orange-crowned Warbler, a Rough-legged Hawk, and a Short-eared Owl. Members that year were treated to a tremendous spring warbler migration and a “remarkable invasion” of Purple Finches during a November blizzard. Lectures at the Brookline library or the Museum of Science, on topics such as “Gulls: Good or Bad Birds?” and Henry Beston’s talk on “Birds of the Maine Lakes,” drew crowds of up to 500.

As our nation entered World War II, the BBC was reaching the end of an era. In 1941, after 15 years, Talbot stepped down as president, replaced by T. E. L. Robinson and then Morton Cummings. The publication of Bird News was discontinued in 1943. In the last issue, Talbot recalled the “wandering voices” of birds he’d never tracked down, particularly a Barn Owl he’d recently missed at Fresh Pond but hoped to find sometime, somewhere. The bulletin-which became blue in 1941 (except for a lone leucistic book in 1945)-was reduced in scope, listing walks and statistical reports but without the poetry and conservation appeals. The report for 1943, the club’s 30thanniversary year, noted 386 members; a high day count of 78 species in Ipswich and Plum Island in May; a high participant count of 42 on the traditional New Year’s Day Ipswich trip; and a total of 128 walks and 227 species. Black-headed Gull, Little Gull, Western Gull and Acadian Chickadee were write-ins on the Mass Audubon state checklist. The checklist at that time, based on the 1931 AOU checklist, included 277 species. Absent from it were Snow Goose, Manx Shearwater, Snowy Egret, Glossy Ibis, Turkey Vulture, Clapper Rail, American Oystercatcher, Wilson’s Phalarope, Forster’s Tern, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Tufted Titmouse, Hooded Warbler, Worm-eating Warbler, Northern Cardinal, and House Finch (not mentioned by Forbush even as a vagrant). A few species now lumped were then split: Common and Red-legged Black Duck, Eastern and Western Willet, Northern and Prairie Horned Lark, Western and Yellow Palm Warbler, and Savannah and Ipswich Sparrow.

In 1943 the consensus bird of the year was a Gyrfalcon in Newburyport; in 1944, a stunning Gray (White-tailed) Sea-Eagle, also in Newburyport. That year the BBC offered 142 trips, finding a record 236 species. But the last few years of the war were also a time of security regulations, rationing, and restrictions on “pleasure driving.” The traditional boat trip to Provincetown in 1944 stipulated “without glasses.” Eventually all boat trips were suspended, and there were no more walks along the coastline. Birders wandering about with binoculars were sometimes suspected as spies or saboteurs assisting German submarines. The club struggled to find trip leaders. The birds were still there, but for many birders, both at home and in ships and trenches overseas, the birds would have to wait. It was not a time for celebration, but as it moved into its fourth decade, the BBC still had much to celebrate-and cause for pride and optimism-and the club would continue to thrive and grow in the postwar years.